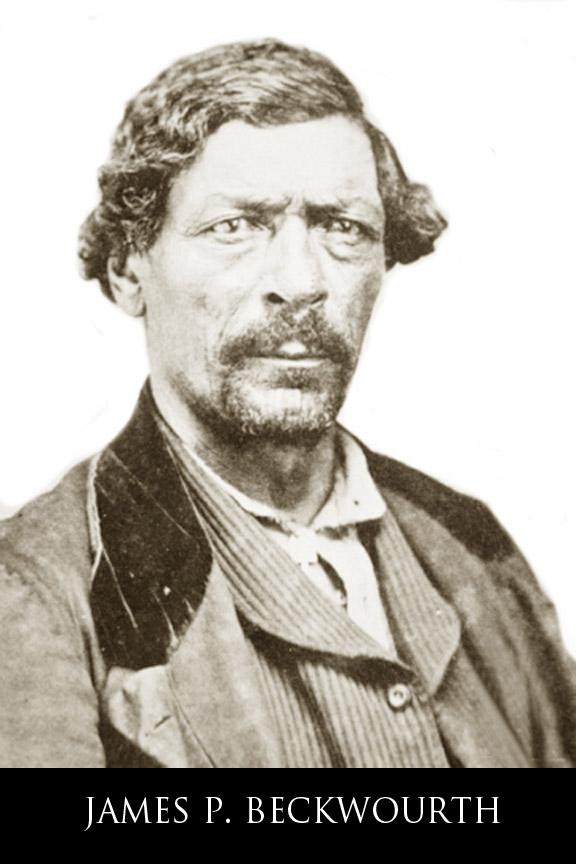

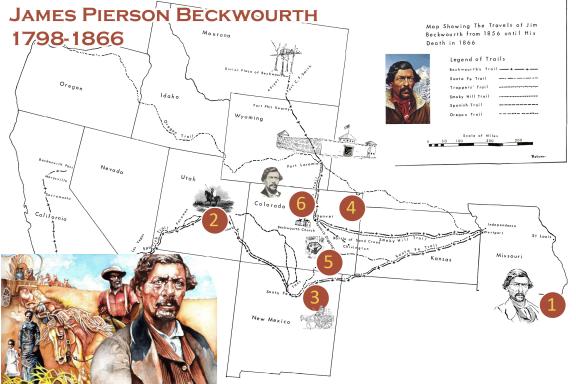

In 1835, Beckwourth embarked on a fur trading expedition that took him through the Santa Fe Trail with Fort Vasquez as the destination. “[Beckwourth] immediately set out to establish himself among the Cheyenne. Through a Crow interpreter, he put on a display of braggadocio for the astonished Indians, playing on their pride and respect for the brave deeds of enemy warriors.

“ ‘William Bent, who was trading in the same village, had just one comment for Beckwourth: “You are certainly bereft of your senses. Indians will make sausage-meat of you.’

But the braggadocio worked (That and two ten gallon kegs of whiskey.) Thanks to Beckwourth’s skill, [the trappers] had a successful fall and winter trade, and made enough to pay off debts and outfit the next season’s trade. But the following winter was disappointing, and they sold out in 1840.

“Beckwourth soon found himself in the employ of the Bent brothers, dealing with the same tribes as before. His friendship with the Cheyenne was cemented and woud last for many years. But he soon began to tire of the monotony of his life, and he set out with a companion over the rugged passes and down into Taos, New Mexico, where he formed a partnership with a friend and set out once again to trade with the Cheyenne, this time on his own account.

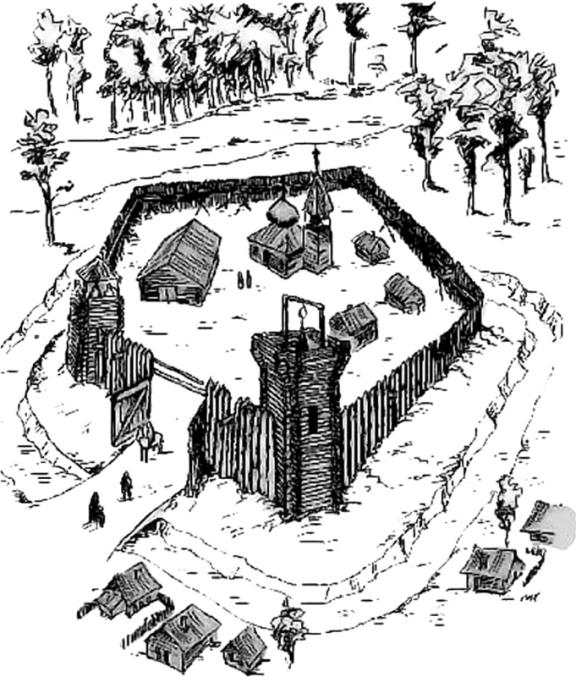

“In October, 1842, Beckwourth took his wife north to the Arkansas in what is not Colorado, where he built a trading post. They were soon joined by twenty or thirty settler families, and a triving community was born” (Beckwourth on the Santa Fe Trail).

“Beckwourth on the Santa Fe Trail.” Jim Beckwourth on the Santa Fe Trail, www.beckwourth.org/Biography/santafe.html#brag.